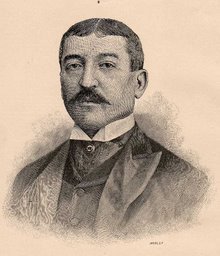

A hundred years ago to this day, on December

8, 1917, a remarkable restaurateur died in New York City - unnoticed by the

public: Alessandro Filippini (or Alexander Filippini, in the anglicized form),

one of the most influential chefs in the famous Delmonico's restaurants. Like

the Delmonico brothers themselves, he was an emigrant from the Ticino in

Switzerland who settled in the New World in the second half of the 19th Century

and left his footprints there.

Filippini's biography remained elusive until now.

We knew about his cook books, but on a personal level not even basic personal

information was available, and books on food history and related websites

contain mostly erroneous dates.

Extensive research in archives and in the New York Public Library enabled

me however to sketch out a fascinating biography:

Alessandro Filippini was born on New Year's

Eve of 1849 in the little village of Airolo in the Canton of Ticino in the

Italian speaking southern part of Switzerland - merely 10 miles north of Mairengo,

the village where the Delmonicos came from. Hardly in his teens, he was sent to

one of the famous cooking schools in Lyon, France, as an apprentice. He was so

talented that the school hired him as a teacher while still in training - which

allowed him to pay for the school. After first professional experiences in

Germany and Switzerland, he arrived in New York City on board of the steamer

'Ville de Paris' on June 5, 1866. He immediately found employment at

Delmonico’s 14th street restaurant

and served under the regiment of Charles

Ranhofer, the French chef who was in charge of the Delmonico kitchens since

1862.

At Delmonico’s for only two months, the young

cook already learned what it meant to be in the kitchen of the city’s most

famous restaurant: President Andrew Johnson was visiting New York, and of

course it was at Delmonico’s that the citizens of the city hosted the dinner in

his honor on August 29, 1866. It was „the finest dinner with which I ever had

anything to do”, Filippini much later told a journalist.

In 1885, just after the death of the great

Charles Delmonico (who was succeeded by Charles C. Delmonico), Filippini began

collecting and writing down the recipes used in the Delmonico kitchens, and

after five year’s work he published it in book form as “The Table”, or “The

Delmonico Cook Book” (1889). Not only did Filippini give a bill of fare for the

three meals of each day of the year, with the corresponding recipes, but also

extensive advice about the seasonality of all kinds of foods and about how to

set a table and how to serve the food.

From the restaurant at 14th Street, Filippini

went on to their Broad Street Restaurant (until 1883), then to their Pine

Street Restaurant, and when that closed in 1889 he moved to the new Delmonico’s

restaurant at 341 Broadway. He soon

became one of the pillars of the Delmonico empire. As a journalist of the New

York Tribune noted in 1891, Filippini "has been at one and at all times

the manager, the buyer and the inventor of toothsome dishes. Every morning for

twenty-five years he arose in time to visit the markets by 3 o’clock, where he

purchased the daily supplies for all of the Delmonico restaurants, uptown and

downtown. No man ever knew better than he the value of food products, and none

could buy so well for his employer. Every day he visited the various

restaurants, studied their needs, made suggestions and improvements in the

service, and kept everything running with perfect smoothness. Not an hour of

the day was he ever idle, and his black hair has become silver-streaked in his

long service."

When in 1890 Charles Delmonico decided to

close the restaurant at 341 Broadway, Filippini regarded this as an opportunity

and opened a restaurant of his own – Filippini’s – just a block away, at 337

Broadway. Filippini told the press that he “intended to keep only the best

food, wines and other beverages”. The New York Tribune, in view of the opening

of Filippini’s, anticipated that “the restaurant, which will be run on the same

plan as Delmonico’s, is destined to have many patrons.”Alas, it did not, and in

May 1893, Filippini had to close Filippini’s Restaurant and make an assignment

of his property for the benefit of creditors. During the short life of his

restaurant, the chef and owner however found time to put out three more

cookbooks: “One Hundred Ways of Cooking Eggs” (1892), “One Hundred Ways of

Cooking Fish” (1892) and “One Hundred Desserts” (1893).

He may actually have been out of work for some

years until around 1898 when he entered into the services of the International

Navigation Company (later renamed International Mercantile Marine). His new

employer was the large conglomerate, backed financially by the banker J. P.

Morgan, that owned and operated at one point 188 ships, including the American

Line, the Red Star Line, the White Star Line and half of Holland America. He

became the “travelling inspector of the American liners”, called in to systematize

steamship cooking on a new basis. He reportedly got on board a ship without

previous arrangement, not being expected, and watched the preparation and

serving of meals, showed the cooks and bakers essential details, and also made

sure that the table stewards were in good training. Moreover, he also oversaw

the composition of the menus served on board, evidently his core competence.

Armed with a letter of introduction to United

States consuls in all parts of the world, obtained from Secretary Hay at the

instance of Senator Chauncey Depew, in 1902 Filippini went on a trip around the

world, starting in Honolulu in January and ending in Paris in September of that

year. He travelled through Japan, China and Hong Kong, the Philippines,

Singapore, India, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Austria, Germany,

Belgium and his old country, Switzerland. By visiting innumerable hotels,

restaurants and private homes, he gathered over 3,300 recipes that he arranged

to form suggestions (as in “The Table”) for “complete menus of the three meals

for every day in the year” and published them as “The International Cook Book”

(1906).

Very little is known about his private life.

Filippini lived most his life in New York City, for the better part with two

sisters and a brother, who also emigrated from Switzerland. The busy life at

Delmonico’s and then the long periods on board of the ships seem to have

prevented him from marrying, but quite late in life he met Julia Martinoli, a

Swiss widow seventeen years the younger, who became his companion, and in 1898

their daughter, Alice Filippini, was born. Alessandro Filippini died on

December 8, 1917 in New York City, at age 67. Neither a report nor an obituary

was published in any of the newspapers. Adamant New York had already forgotten

about him.